• Part 1: An Overview

• Part 2: Towns & Villages along the Southern Rhône River

• Part 3: Best Places to Visit near the Southern Rhône River

The Ultimate Guide to the Southern Rhône River

Part 1: The Southern Rhône River – An Overview

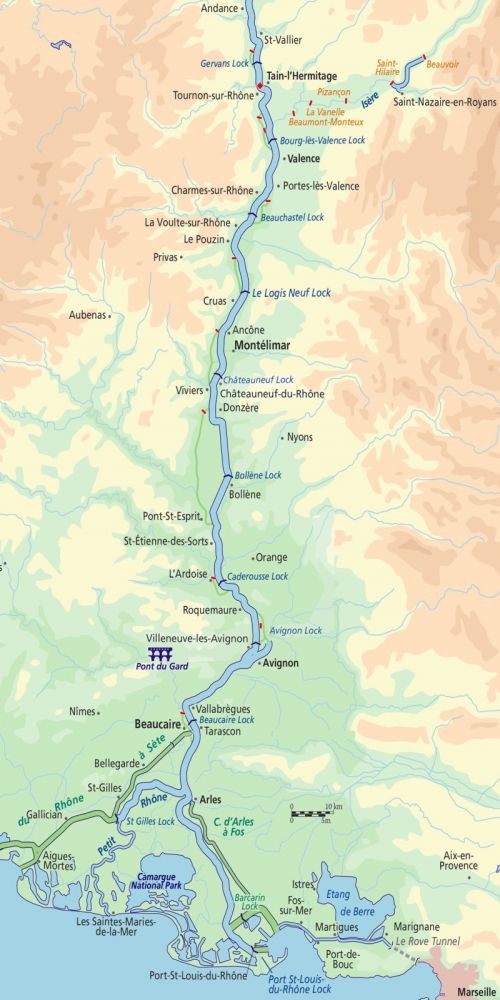

The River Rhône is one of the major rivers of Europe. It rises in the Swiss Alps, passes through Lake Geneva and then runs through south eastern France. At Arles, near its mouth on the Mediterranean Sea, the river divides into two branches, known as the Grand Rhône and the Petit Rhône. The resulting delta constitutes the Camargue region.

Before railroads and highways were developed, the River Rhône was the main inland trade route, connecting the cities of Arles, Avignon, Valence, Vienne and Lyon to the Mediterranean ports of Fos-sur-Mer, Marseile and Sète. It also helped spread Greek and later Roman influence from the Mediterranean to western, central and northern Europe. In particular, it aided the spread of a specific confectionery now most associated with the city of Montélimar – nougat.

Navigation was difficult as the river suffered from fierce currents, shallows, floods in spring and early summer when the ice was melting, and droughts in late summer. Until the 19th century, passengers travelled in coches d’eau (water coaches) drawn by men or horses, or under sail. Most travelled with a painted cross covered with religious symbols as protection against the hazards of the journey, and usually had small statues of Saint Nicholas or Saint Catherine, the patron saints of bargees and mariners, respectively.

Part 2: Towns & Villages along the Southern Rhône River

Montélimar, or “the door of Provence”, has been inhabited since Celtic times and was largely rebuilt during the Roman era to include a basilica, aqueducts, baths and a forum. The Via Agrippa, a network of Roman roads stretching from Lyon to important hubs and ports throughout France, played a major role in Montélimar’s development.

Despite a history of food shortages, the town is perhaps most famous for its nougat. The confectionery first appeared in Middle Eastern texts in the 12th century, and it is thought to have been brought to Western Europe by the Phoenicians, as they conquered and founded cities. The story of Nougat de Montélimar, however, started in the 18th century when Olivier de Serresm, an agronomist living in the Ardeches, succeeded in planting almond trees to produce the sweet. He then used the almonds to replace walnuts commonly used in nougat. Traditionally, nougat was baked at home, not by professional nougat makers as it is today. The production process is described in great detail in the Palais des Bonbons et du Nougat, literally “The Palace of Sweets and Nougat”.

Travellers used to buy the nougat on their way to the south of France, as the city is both next to the Rhône and to the primary route the N7. Since the construction of the A7 highway, however, many nougat factories have been forced to close as tourists no longer stop in the city.

Châteauneuf-du-Rhône is a small village on the banks of the Rhône. This area has been inhabited since prehistoric times, with Neolithic remains to the north and a pre-Roman oppidum to the south. Important Gallo-Roman remains have been found bordering the Via Agrippa, with paths leading to the river. During the Middle Ages a town was founded, supported by the abbeys of Lyon and Arles, with two castles, one of which was built on the site of the Roman Oppidum. A church dedicated to Saint Nicholas was built in the 12th century. At the end of the 13th century, the town’s inhabitants obtained a charter, whereupon taxes were regulated, and they enjoyed an active culture of trade fairs and markets. The two castles were ruined in the 16th century.

Donzère is home to the largest known wine cellar of the ancient world, the Villa du Mollard. Excavated between 1981 and 1983, the site encompasses over two hectares and features warehouses with a capacity of 2,500 hl (66,000 gallons) where wine was stored before being transported along the river to the far reaches of the Roman Empire. It dates between 50 – 80 AD.

Bollène has been occupied since ancient times, as suggested by the nearby troglodyte village of Barry, whose structures are believed to have been inhabited continuously from the Neolithic-era to the early 20th century. Overlooking the Rhône Valley, the hill that the village was built on was a strategically chosen site; from the top one can see to the north, west and south and watch for approaching threats. Archaeologists working in the area have found Palaeolithic arrowheads, Neolithic polished stone axes and a collection of other prehistoric tools. Excavations nearby along the Jerusalem Way, a pilgrim path which connects Santiago de Compostela with the city of Jerusalem, have also uncovered Roman burial plots and pottery.

Close to the troglodyte settlement, the medieval village of La Bollène was situated on a rocky outcrop, defended by a castle. In the 14th century a band of marauders led by Raymond de Turenne destroyed the village and its defences. The church, sometimes dedicated to St Andrew or St Vincent, has completely disappeared.

Today, Bollène is most famous for having the largest lock on the Rhône River, with a rise of 23m and also for the Tricastin Nuclear Power Plant.

Pont Saint-Esprit, as its name suggests, is the site of a historic crossing of the Rhône River. The 26-arched bridge was built between 1265 and 1309 and was mentioned by the Irish pilgrim Symon Semeonis in 1323 on his way to the Holy Land: “Pont-Saint-Esprit where there is a famous stone bridge over the Rhône, half a mile in length, the height of which and the breadth of its arches are greatly admired by all those who cross over it”. It is the oldest bridge on the River Rhône and connects Provence to the Languedoc.

In the Middle Ages the town was called Saint-Saturin-du-Port, after its church, but changed its name after the construction of the bridge. The town’s wealth was dependent on tolls enforced on those wishing to cross the bridge and goods carried across were often directly loaded on to barges waiting beneath it. Carts and trolleys were rolled over straw, so as not to cause damage from vibration.

The town features several historic monuments including the 12th century priory and the church of St Peter. Although it was renovated in the 18th century, today it is in a prolonged state of disrepair. The building is no longer used and is unfortunately inaccessible to the public. The 15th century church of Saint-Saturin, however, is the current parish church. Its interior was completely restored in 2008-2009 and the entrance presents an interesting Gothic portal. The beautiful tall bell tower contains three bells, one of which weighs two tonnes! The church organ was made in 1863 by Cavaillé-Coll, a well-known family of organ makers.

St-Étienne-des-Sorts is a village on the left bank of the River Rhône and lies within some of the most mountainous terrain in the area. The first people who came to settle in this region must have been fascinated by its favorable position among the hills, and in fact, several remnants of prehistoric settlements have been discovered nearby. The area was still inhabited during the Roman period, from which at least two religious buildings remain: the parish church on the bank of the Rhône River and the chapel of Saint Pierre on the summit of a nearby mountain.

Its story revolves around the transportation of goods on the river, and barging is a tradition which continues to this day in the village. People from St-Étienne-des-Sorts are known as Stephanois, and built traditional boats called “sapines”, which only needed three or four crew. The villagers made use of the natural resources found in and around the town, transporting the trunks of poplars and other trees up to the sawmills of Avignon, as well as stones taken from quarries, which were used to reinforce the riverbanks. This commerce reached its peak in the early 1880s, when up to 20 boats a day would leave for Avignon, crewed by the men and boys from the village.

In the late 19th century there was a project to dyke and canalize the River Rhône. It took five hundred workers to extract the stones, cart them from the quarries to loading quays and transport the stones by water so that they could be used for construction.

There is not a single part of the river from Pont-Saint-Esprit to Avignon which the mariners of the village did not contribute in reinforcing. The last sapine which navigated the river, was lost in 1912. In the meantime, many of these boats had been replaced by much larger pontoons and towed by steam tugs. As the work on the Rhône River ceased, the resources of the town slowed considerably. The population of 1,000 in circa 1800, gradually fell to 311 inhabitants in 1931. Today, the General Navigation Company seeks to recruit the best barge captains, many of whom still come from Saint-Étienne-des-Sorts.

Roquemaure is a small town situated on the right bank of the River Rhône. The town was the site of a royal castle in the Middle Ages. In 1314, Pope Clement V, the first pontif to be based at Avignon, died at the castle while travelling from Châteauneuf-du-Pape to his birthplace in Gascony. After the French Revolution, the castle was destroyed and now only two towers remain. In the centre of the town, the 14th century church of St John the Baptist is built in the Provençal Gothic style. It contains a bust of Pope Clement V, relics of Saint Valentine and an organ dating back to 1690.

In the 18th century, Roquemaure was the centre of attempts to regulate the production of wine in the area and it was here that the term “Côtes du Rhône” was coined. In 1835 work began on the construction of a bridge over the river at Roquemaure, as there was no crossing between Avignon and the bridge at Pont-Saint-Esprit. The bridge was destroyed by an American aircraft in August 1944. A chain ferry was operated across the river until the current bridge opened in 1959.

The town is infamous as the location at which Phylloxera, a parasite which attacks grapevines, and which ultimately killed 75% of the vineyards in France, was introduced from North America. Viticulture is still an important activity in the town, with several types of wine being produced including some classified as Côtes du Rhône AOC.

Villeneuve-lès-Avignon is located on the opposite bank of the river to the town of Avignon. In the 6th century, the Benedictine abbey of St André was founded on Mount Andaon, and the village which grew up around it took its name. The current town was founded by King Philip IV, also known as Philip the Fair (for his good looks rather than good nature!), and boasts both the 14th century castle he built and a tower to mark the French side of the Saint Bénézet bridge across the River Rhône between the then Kingdom of France and the Papal State of Avignon.

In 1356, the Carthusian monastery Notre-Dame-du-val-de-Bénédiction was founded by Pope Innocent VI, and soon became one of the largest and most important in Europe. During this time the town was also used as a leisure resort for the cardinals of France, while the popes were based in Avignon.

In the 17th century, plaice was heavily fished in the River Rhône, and nets were installed at the foot of the tower of Philip IV downstream of the water mills which ground flour. Fish were attracted by flour which had fallen from the mills, providing a plentiful catch.

ln 1820, the construction of a bridge and the arrival of regular train services once again promoted trade and the establishment of many small factories helped to stimulate the economy. Just as the cardinals had in the 14th century, the families of the Avignon Bourgeois established their holiday resorts in the hills of Montaut, where they enjoyed the beautiful views of Avignon and the heart of the Rhône valley.

Avignon is an ancient medieval city, located on the left bank of the Rhône River. Between 1309 and 1377, during the Avignon Papacy, 7 successive Popes resided in the city and in 1348 Pope Clement VI bought the town from its sponsor, Joanna I of Naples. Papal control of the town continued until the French Revolution, when in 1791 Avignon once again became a part of France. It is now the capital of the Vaucluse department and one of the few French cites to have preserved its medieval ramparts. The historic centre, which includes the 14th century Palais des Papes, the 12th century Romanesque Cathedral of Notre-Dame des Doms d’Avignon and the famous Pont d’Avignon became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1995. Over 170 buildings and sites in Avignon are registered as Historic Monuments.

The “Pont d’Avignon”, St Benezet Bridge, made famous by the song, was built in the late 12th century. Breached several times by the strong Rhone currents, it was finally abandoned in 1680 and eventually replaced by a suspension bridge. Four arches still remain and on one of them is the Romanesque St Nicholas Chapel. The song goes on to sing “on y danse” but in fact, the dancing was on the Ile de la Barthelasse underneath the bridge.

After the persecutions of Christians throughout the Roman Empire, Christianity would have come to Aramon in the first half of the 4th century AD, with the religious-tolerant Emperor Constance-Chlore. His first wife, Helen, was Christian and in 313 his son proclaimed an edict in Milan establishing freedom of worship. The successive invasions of the Visigoths, Saracens, Normans and Hungarians did not spare the city. Built on the banks of the Rhône River, it was easily attacked by groups of invaders making their way down one of the major routes through France.

At the time of the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire in the 10th century, the town became one of the “doors of the Languedoc”, in part due to its port and, in the 14th century the proximity of Avignon and the Papal territories. A toll on the island of Carlamejean opposite Aramon, forced boatsmen to pay a tax on transported goods, especially on salt travelling from the Camargue to Savoy. The proceeds were shared between the King and the lords of the town.

The town suffered during the Wars of Religion, the 16th Century conflict between the Catholics and Protestants, and changed sides several times. Bullet marks on the cliff walls can still be seen. In 1567, the Protestants were finally driven out of the town, and a Catholic garrison of 60 soldiers moved into the city.

Under the Duke of Sully, the population grew and then, under Colbert, the wealth of the town expanded exponentially. It was during this time that St Martin’s Fair was founded, and still exists to this day.

The next two hundred years brought plague in the form of the Black Death and many floods and harsh winters before the arrival of the railway from Nimes to Teil in 1878 brought back prosperity to Aramon. The cultivation of cereals gave way to market gardening and fruit crops. A daily market from April to November was created. The craft industry also prospered with wickerwork workshops using wicker harvested on the islands along the Rhone River.

The suspension bridge that replaced the ferry in 1900 was destroyed on August 15, 1944 by five successive waves of bombers, was rebuilt and inaugurated on February 20, 1971. The twentieth century saw the establishment of new industry. The nuclear power station in Aramon, whose chimney is 250m high, is the tallest structure in the Languedoc region.

Vallabrègues is a small village opposite the town of Beaucaire, on the left bank of the River Rhône. Being an ancient medieval village, its streets are generally too narrow for cars and so the locals get around either on foot or by bicycle.

A tradition of basket weaving is found here. Vallabregues was once the biggest basket producer in France, when the wicker container was widely used for the transportation of goods. The village’s proximity to the river ensured that reeds growing nearby were used to weave after soaking them. Nowadays, the industry is fast disappearing although every year a festival is held and homemade baskets from all of Europe are displayed in front of the houses. A museum commemorating the tradition can be found in the village.

Founded in the 7th century BC, Beaucaire was widely known as a staging post of the Via Domitia connecting Italy to Spain, with a reputation as a trade town that has lasted nearly 2000 years.

Part 3: Best Places to Visit

Founded in 35 BC by the veterans of Second Legion, Orange was first known as Arausio, and was originally a Celtic settlement named after the local god of water. A major battle, known as the Battle of Arausio, was fought nearby in 105 BC between two Roman armies and the Celtic Cimbri and Teutines tribes, which resulted in one of the Roman army’s worst ever defeats. However, after the battle, the Celtic army moved on and life in Arauso continued. The Roman town covered an area of 70 ha and its inhabitants enjoyed civic monuments, including a forum, temple complex and theatre, which is still visible today.

Arausio was the capital of a wide area of northern Provence, which was divided up into lots for the Roman colonists. It was likened to a miniature Rome, with many of the public buildings that would have been familiar to Roman citizens. The town prospered, but was later sacked by the Visigoths in 412.

It had, by then, become largely Christian and from the end of the 3rd century constituted the Ancient Diocese of Orange. In the 12th century, Orange was raised to a minor principality as a fief of the Holy Roman Empire.

When William the Silent, Count of Nassau in the Netherlands, inherited the title of Prince of Orange, the principality was incorporated into the holdings of what was to become the House of Orange-Nassau. This meant it sided with the Protestants during the French Wars of Religion, during which the town was badly damaged. In 1568, the Eighty Years War started with William leading the bid for Dutch independence from Spain. He was subsequently assassinated in Delft in 1584 but his son solidified the independence of the Dutch state, whose United Provinces survived to become the Netherlands, still ruled today by the House of Orange-Nassau.

William, Prince of Orange, ruled England as William III and the town then gave its name to other Dutch-influenced parts of the world including the Oranges in New Jersey and the Orange Free State in South Africa. Orange remained part of scattered Nassau holdings until it was captured by the forces of Louis XIV in the late 17th century and finally ceded to France in 1713 under the Treaty of Utrecht.

Today Orange is still renowned for its Roman architecture. The Roman theatre is described as the most impressive of its kind in Europe. The fine Triumphal arch of Orange is believed to date from the time of Augustus or Tiberius and the arch, theatre and surroundings were listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage site in 1981. The city museum displays the largest Roman maps ever recovered, which are etched in marble. Measuring 8 x 6 metres, they depict the area between Orange, Nîmes and Montélimar.

Nîmes, the most Roman of any city outside Italy, is located between the Cévannes mountains and the Mediterranean. With a rich history dating back to the Roman Empire, the city has many famous monuments including the Nîmes Arena and the Maison Carrée. Because of this, it is often dubbed the French Rome. Nîmes is perhaps also known for its tradition in textiles – the now ubiquitous blue jeans originated from the city and the word denim comes from the cloth used by the Romans as saddles for horses and sails for ships. The “Serge de Nîmes”

Nîmes became a Roman colony sometime before 28 BC, according to the earliest coins found in the area. The settlement was already under Roman influence, though it was Augustus who made the city the capital of the Narbonne Province, and brought the city its glory. The Emperor gave the town a ring of ramparts 3.7 miles (6km) long and reinforced by 14 towers, two of which remain today. An aqueduct was built to bring water from the hills to the north, and where it crossed the River Gard between Uzes and Remoulins, the spectacular Pont du Gard was built. The Maison Carrée is one of the best-preserved temples to have been found in the former Roman Empire, and later inspired the design of the Virginia State Capitol at Richmond. Although nothing remains of other monuments, their existence is known from inscriptions on architectural fragments found over the course of excavations. The amphitheatre dates from the end of the 2nd century and was one of the largest in the Empire.

After the Roman period, the Christian Church, which had already been established in Gaul since the 1st century AD, appeared to be the last refuge of classic civilisation. It was remarkably organised and directed by a series of Gallo-Roman aristocrats. When the Visigoths were accepted into the Roman Empire, however, Nîmes was included in their territory and the urban landscape went through much transformation, but the heritage of the Roman era remained largely intact.

By 725, the Saracens had conquered the whole of the Visigothic territory including Nîmes. The Muslim government lasted until 752, when the Frankish king Pepin the Short captured the city, but by then, Nîmes was only a shadow of the opulent Roman city it had been.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, the Rhône Valley went through an uninterrupted series of invasions which ruined the economy and caused long-lasting famines. Customs were forgotten, religious tensions and epidemics all affected the city. By the mid-17th century, however, Nîmes experienced a period of prosperity. Population growth caused the town to expand, slum housing to be replaced and the reconstruction of the aging Notre-Dame-Saint-Castor, which had been built on the site of the temple of Augustus. The Quais de la Fontaine, the first civic gardens of France, were laid out, areas surrounding the Maison Carrée and Amphitheatre were cleared of intrusions and the entire population benefited from the atmosphere of prosperity as the renaissance strengthened the manufacturing and industry of the city.

Following a European economic crisis that hit Nîmes with full force, the French Revolution awoke demons of political and religious hostility. The White Terror, a period where people who were suspected of having ties with the revolutionary party or were considered Bonapartists and subsequently arrested or murdered, following the return of Louis XVIII to power, added to the natural calamities and economic recession. Order was restored in the course of the 19th century and Nîmes once again became the primary metropolis of Bas-Languedoc, diversifying its industry of textiles into other sectors.

During WWII, Nîmes was a centre for French resistance activity and later, in 1944, the Nîmes marshalling yards were bombed by American planes. The 2nd Régiment Étranger d’Infanterie, the main motorised infantry regiment of the French Foreign Legion, has been garrisoned in Nîmes since November 1983.

Arles is a city located close to the mouth of the River Rhône. The city has a long history and was of considerable importance in the Roman province of Gallia Narbonensis. The Roman and Romanesque monuments of Arles were listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites in 1981.

The Romans took control of the town in 123 BC and expanded it into an important city with a canal link to the Mediterranean constructed in 104 BC. It struggled, however, to escape the shadow of Massalia further along the coast. Its chance came when it sided with Julius Caesar against Pompey. Massalia backed Pompey but when Caesar emerged victorious, it was stripped of its possessions, which were transferred to Arles as a reward. The town was formally established as a colony for veterans of the 6th Roman Legion, which had its base there.

Arles was of considerable significance in the province of Gallia Narbonensis. It covered an area of some 40 ha (100 acres) and possessed a number of monuments including an amphitheatre, triumphal arch, Roman circus, theatre and a full ring of ramparts. Ancient Arles was a lot closer to the sea than it is today, and served as a major port. It had, and still has, the southern-most bridge on the Rhône, and unusually the Roman bridge was not fixed but consisted of a pontoon-style bridge held together by boats, with towers and drawbridges at each end. This unconventional design was in direct response to the river’s frequent violent floods, which would have made short work of a fixed crossing.

The city reached a peak of influence during the 4th and 5th centuries, when Roman Emperors frequently used it as their headquarters during military campaigns. In 395 it became the seat of the prefecture of the Gauls, governing the western part of the Western Empire, as was the philosopher Favorinus, as the city became renowned as a cultural and religious centre during the late Roman Empire.

In 735, after having raided the Lower Rhône, Andalusian Saracens moved into the city. The following year the Prince of the Franks, Charles Martel, campaigned south, attacking and capturing Arles after destroying Avignon. In 739, Charles drove the Saracens away and brought Provence to heel. In 855 Arles was made the capital of the Frankish Kingdom of Arles, which included Burgundy and part of Provence, but was frequently terrorised by Saracen and Viking Raiders. Though successive leaders counted themselves kings of Arles, few went to be crowned in the cathedral. During these troubled times, the amphitheatre was converted into a fortress, with watchtowers built at each of the four quadrants and a small walled town constructed within.

The town regained political and economic prominence in the 12th century, with the Holy Roman Emperor Frederik Barbarossa travelling there for his coronation in 1178. During that same century, it was a free city governed by an elected chief, who appointed consuls and other magistrates. It retained this status until the French Revolution of 1789.

Arles had an important Jewish community between the Roman era and the end of the 15th century with the first Jews coming as exiles from Judaea after Jerusalem fell to the Romans. The city played a major role in the work of Jewish scholars, translators and philosophers, who were most important to the faith during the Middle Ages. The community lived relatively peacefully until they were expelled from the city never to return. Jewish archaeological artefacts and texts are today found in the local museum.

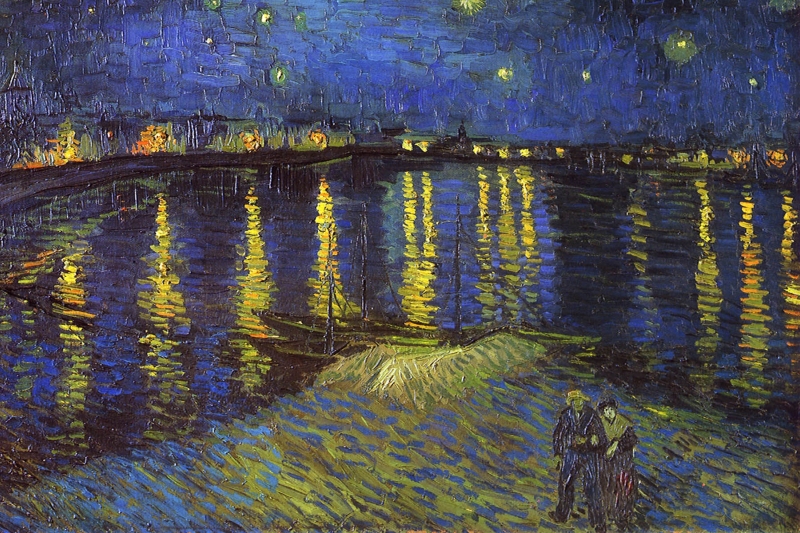

Arles was economically important as a major port on the Rhône River until the arrival of the railway in the 19th century all but ended the river trade. The painter Vincent Van Gogh arrived there in February 1888, fascinated by the Provençal landscapes, and produced over 300 works during his time in the city including The Night Café, the Yellow Room, Starry Night Over the River Rhône and L’Arlésienne. Paul Gauguin visited him there; however, as Van Gogh’s mental health deteriorated, he was admitted to the Old Hospital of Arles. The concerned Arlesians signed a petition the following year, demanding the painter be confined and in May 1889 Van Gogh took the hint and left Arles for the Saint Paul asylum in St-Remy, where he stayed until a few months before his death in 1890.

English

English

Spanish

Spanish French

French German

German Norwegian

Norwegian Portuguese

Portuguese Swedish

Swedish Italian

Italian Russian

Russian Simplified Chinese

Simplified Chinese Japanese

Japanese