Part 1: An Introduction to Whisky

Part 2: Whisky & Terroir

Part 3: Whisky Flavours

Part 4: Tasting Whisky

Part 5: The Art of Blending

A Beginner's Guide to Whisky

Part 1: An Introduction to Whisky

Whisky is fascinating. There are hundreds of variations, yet very few whiskies taste alike. Ardbeg and Laphroaig are both single malt Scotch whiskies and are made in distilleries located a stone’s throw from each other on the island of Islay off Scotland’s western coast and yet their flavours are remarkably distinct. Each whisky reflects the ingredients, machines and the people who make it. Recipes are revised with changes in the water, soil and grains and whisky-makers age and are eventually replaced by new generations. New brands of whisky are born, old brands die while others are resurrected. So, a bottle of Bruichladdich Scotch whisky produced in 2010 will not taste exactly the same as one produced in 2050. For the curious soul, then, whisky provides endless opportunities for discovery, as it ever evolves.

As with much in the world of whisky, there is a lot of nonsense propagated about the correct usage of the terms “whisky” and “whiskey”. Whereas some insist that “whiskey” refers to the drink produced in the United States, this is not true – as can be seen by looking at a bottle of the American-made Old Forester Kentucky Straight Bourbon Whisky. Generally, in Canada, England and Scotland the preferred spelling is “whisky”, whereas in Ireland and the USA it is “whiskey” but plenty of exceptions to these rules exist. In this chapter, the term “whisky” is used as a catch-all term covering both “whisky” and “whiskey”.

Put simply, “whisky” is an alcoholic beverage that is distilled from fermented cereal grain and aged in wooden casks. The term “cereal grain” refers to seed producing grasses that we farm for consumption, such as barley, corn, oats, rye, wheat and so on. Barrel ageing is included as an essential part of the definition of whisky because barrel-ageing imparts colour (from straw yellow to deep brown) and flavours, such as vanilla, to the whisky. Taken together, these two characteristics differentiate whisky from other distilled spirits, such as cognac (which is distilled from fermented grape juice) and vodka (which can be distilled from grain, sugar beets or nearly anything else, but is not barrel-aged).

Two processes are required to produce whisky – fermentation and distillation. In simplest terms, fermentation is the production of alcohol from sugar, yeast, and water. Beer and wine are also produced through fermentation, but instead using grains and grapes. In the case of wine, grapes are crushed to release their sugary juice and yeasts either on the grape, or added by the winemaker, feast upon the sugars, producing carbon dioxide gas and alcohol. With beer, an additional step is required. Before the yeasts can work, the grains must be cooked in hot water to release their sugars.

Distillation is the process of heating a liquid to its boiling point, capturing its vapours, and condensing them back into a liquid. So then, whisky-making might be conceived as the fermentation of grain and water into beer and the distillation of that beer into liquor or distilled spirit. Whisky-making, then, is simple, right? Make beer boil, catch its boozy vapours, and let them condense into liquor and – voila! Anyone can do it! Well, yes and no. Making foul tasting, throat burning bad whisky is quite easy. Making delicious, sense delighting, good whisky is extremely challenging.

Many have tried, and only a few have succeeded due to the numerous factors that can immensely affect the taste of the final product, for better or for worse.

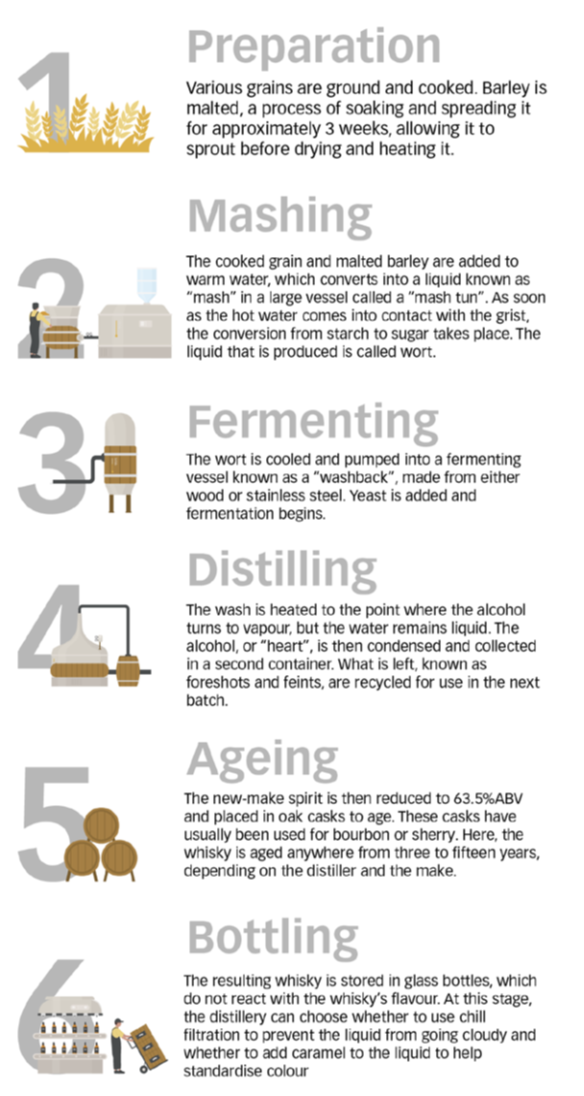

These factors include the character of the water employed in the process, the quality, quantity and type of the yeast(s) and the grain(s) used, the shape, structure and mechanics of the still used and the number of times the whisky is distilled. After distillation, maturation carries a myriad of additional factors such as the length of time the whisky will be aged, the specific characteristics of the cask in which it is aged – including its size, the type of wood from which it was made, the condition of the cask’s interior (new, charred, previously used to hold another beverage such as sherry or bourbon) and the microclimate of part of the warehouse in which the cask was stored. Additionally, the whisky-making process itself is inherently challenging – a marriage of chemistry and craftsmanship comprising of four vital stages: grain preparation, fermentation, distillation and the maturation and bottling, all of which must be carried out with great care in order to produce a palatable whisky.

Every distillery has its own methods and styles and what follows is a simplified overview of the process.

In order to get spirit from seeds, the whisky-maker must take a hard starchy seed and transform it into sugary material that can be fermented and distilled.

Malt Production

While single malt distilleries follow the same process, each one will have a different variation on malt production. It is this individual approach, specific to each distillery, which gives each single malt its distillery character. Though the distiller will make personalised decisions throughout the process, the main stages of whisky production are explained in the following graphic.

Part 2: Whisky & “Terroir”

The idea that grapes taste the way they do because of the combination of site-specific influences – the geology, the microclimate, the soil – is known as the grape’s ‘terroir’, and its advocates say it is why grapes from one vineyard produce legendary wines while those in the vineyard next door are good only for plonk.

For years, the question has been asked: does what works for wine also work for whisky? If grapes bear the taste of where they came from, could the barley used for single malts also carry the flavours of its individual field? Is there such a thing as terroir for whisky?

Terroir, from the French “terre” meaning “land”, is the set of all environmental factors that affects a crop’s phenotype, including unique environment contexts, farming practices and a crop’s specific growth habit. Collectively, these contextual characteristics are said to have a character; terroir also refers to this character. Terroir encompasses Pedology (the study of soil), geography, edaphology (the science concerned with the influence of soils on living things), microbiology, solar radiation, meteorology and much more. It is about the importance of place and the significance of where something comes from – whether it be a vineyard or a whisky distillery.

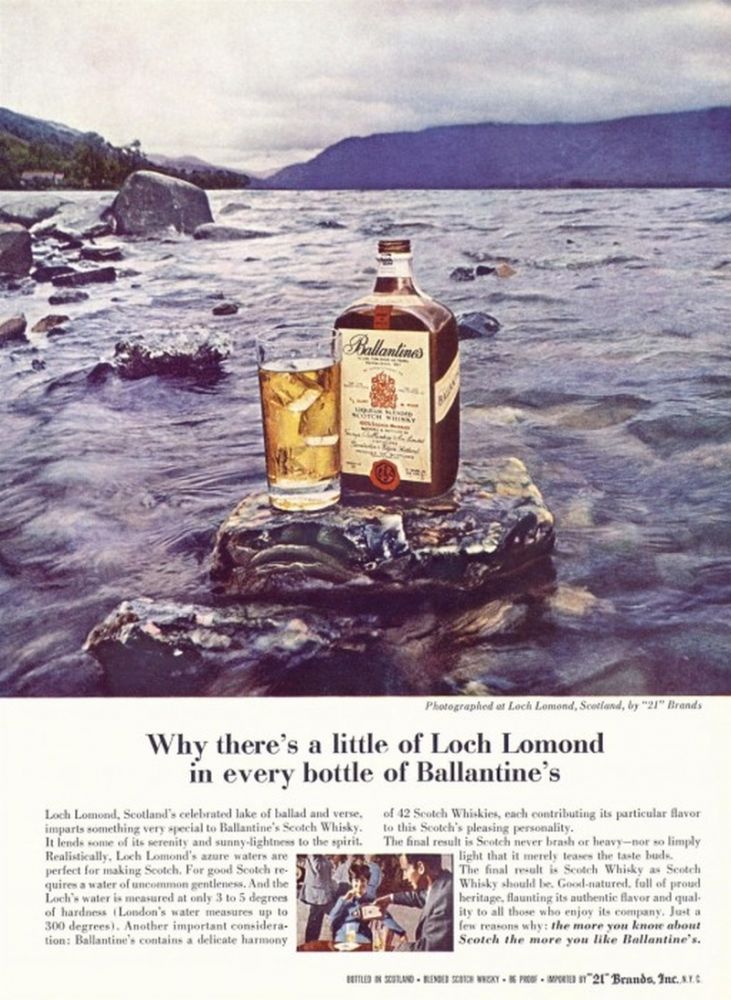

Whisky advertisements have, for centuries, been awash with heather-clad hills, babbling burns, and storm-lashed coastlines. The message has been clear: drink this and you get flavours drawn straight from the Scottish landscape. It’s a romantic notion that was given further support by the late whisky writer Michael Jackson. Writing in his Malt Whisky Companion, he spoke of whiskies as “real, evolved drinks” that arise from “their own terroir: geology, soil, vegetation, topography, weather, water and air”.

Even within a geographical area, such as Dufftown in Scotland, distilleries will have their own terroir. Forests have terroir, as do the species of oak that grow in them and varieties of barley in adjacent fields. But terroir is also about man’s interaction with the land and, from a drinker’s point of view, a deeper and conscious understanding of an environment will give deeper appreciation of the whiskies.

“Scotland’s heather-clad hillsides, its peaty moorlands and its seaweed-fringed islands all contribute to the character of its national drink. To sample some of the more pungent malt is to taste the terroir” continues Jackson.

He identifies the rock, the snow, the water, the peat, the heather, the barley, and the seaweed as the factors that make up the terroir, which together with the distilling and maturation techniques deliver the flavour of the whisky. For one thing, Jackson’s all-embracing definition of terroir refers more to the finished whisky than where the barley was grown, dealing more with broad regional characteristics than local produce. Whiskies are often referred to by their regions – a Speyside style, an Islay malt: could that be what terroir means for whisky?

It depends who you talk to, but perhaps the best-known proponent of developing the concept of wine-style terroir for whisky is Mark Reynier, the former Managing Director of Bruichladdich Distillery on Islay. To him, the terroir is all about the barley and has nothing to do with regionality. “When you get whiskies made from barley imported from who knows where, and then matured in a warehouse in central Scotland and bottled in a factory in Glasgow or Edinburgh, the idea of regionality doesn’t make much sense,” he says.

“Terroir refers to the prime commodity whisky is made from, which is barley. Any farmer will tell you that different parts of their property are more-or-less productive, higher yielding, more disease resistant, have finer soils, or are better exposed.”

Not everyone who makes whisky, however, is quite so keen to embrace the concept. Just up the road from Bruichladdich, Kilchoman Distillery also boasts of a “barley-to-barrel” approach, going so far as to grow a lot of its own barley on a farm attached to the distillery. The Kilchoman distillery doesn’t agree with terroir, claiming that “malting barley is malting barley, and terroir doesn’t have a huge effect like it does with wine. The same grape varieties grown around the world taste different, but I would be hard pushed to tell you I can tell the difference between one type of barley grown in this field and another kind of barley grown in another field”.

In Speyside, the global ambassador for The Glenrothes, Ronnie Cox, sees terroir as linked to the idea of regional whiskies, which he calls something of a throwback to a century or more ago, when the terroir had some importance to the taste of the whisky. “Today” he says, “about 70 per cent of the flavour of non-peated whiskies comes directly from the interaction of the spirit and the cask, whereas in those days it was much more to do with the spirit itself.”

The influence of different types of casks, different finishes, using single or double casks, or by producing vintages only, gives distilleries scope to craft various styles and varieties of whisky.

According to Fred Revol at the Domaine de Hautes Glaces, in France, “Terroir can be misinterpreted as being hands-off, that the soil gives everything and that man is irrelevant. It’s not true. It’s not just soil and altitude, but process and know-how. It is something made by being in a place at a time”.

This should apply to all whisky and those who distil mindfully will make a better product. But whisky is more than a product – it is a distillate of time and place, as well as the person making it. That’s terroir.

Part 3: Whisky Flavours

We, as humans, smell our way through our lives. Aromas help us make sense of the world and we do it without consciously realising this. The fragrance specialist at Givaudan, Dr Roman Kaiser, argues that there was a deliberate relegation of the sense of smell in the 18th and 19th centuries when philosophers argued that sight was the superior sense whereas smell was “a primitive, brutish ability associated with savagery and even madness”.

It is also the case that we simply forget to consciously smell things as we get older. We know what a flower smells like, and so why differentiate between a daffodil and a freesia? The fact that so many of the pictures that appear in our minds when we concentrate on a glass of whisky comes from our childhood, shows us that at some point in our lives we did take the trouble to inhale.

Flavour – by which we mean aroma and taste – is ultimately how we differentiate between whiskies. We may be tempted by the packaging, or find the price attractive and we may be led astray by the region but the main reason for buying a glass or bottle of whisky is because we like the taste. But what does the picture in our heads as we taste the drink mean? The aroma of vanilla, of crème brûlée or of coconut or pine tells us that the whisky has been matured in American oak. Aromas of dried fruits and cloves, however, suggests a cask which once held sherry has been used. Images of Spring meadows – green grass and tree blossom – speak of a long, slow distillation with plenty of time for the vapour to come into contact with copper and with aromas which bring to mind roasted meats indicates the spirit had a short amount of contact with copper and potentially the use of worm tubs.

If you have trouble identifying aromas and images while tasting a whisky, close your eyes and try to think of a season. Not only will the aromas snap into focus but they will give you a clue as to how best enjoy the whisky

– spring-like and the whisky should be enjoyed with ice before a meal, rich and autumnal then perhaps slowly and after dinner.

No spirit on earth has such a rich and complex array of aromas, spanning a spectrum from whisper light to heavily peated and all the points in between. Whisky should not be viewed as a brand, but as a flavour package. As soon as you understand flavour, you will understand whisky.

Part 4: Whisky Tasting

We all know how to taste. If a plate of food was set in front of you, you would most likely have an immediate opinion about it, but if a glass of whisky was placed there instead, would you find the words to describe the tastes and aromas as easily?

Whisky is currently in the same position wine was in, 20 years ago. There is a latent desire to try it, but the average consumer does not have the language with which to describe what he or she wants and, instead of helping, words have become a barrier.

When tasting whisky, it is a good idea to have some “umbrella” terms or groups of words which can accommodate several taste and smell profiles. Below are listed some to help get you started.

Fragrant and Floral

The aromas found in these whiskies bring to mind fresh cut flowers, fruit blossom, cut grass and light green fruits. On the palate they are light, slightly sweet and often with a fresh acidity. They are ideal as an aperitif before a meal but could equally be treated like a white wine – served chilled in wine glasses.

Malty and Dry

These whiskies are drier on the nose. Crisp, biscuity, and sometimes dusty with aromas that remind you of flour, breakfast cereal and nuts. The palate is also dry but is normally balanced by sweet oak. Again, these are good for an aperitif or even breakfast whiskies!

Fruity and Spicy

The fruits conjured up here are ripe orchard fruits such as peach, apricot and, perhaps something a little more exotic, mango. These whiskies will also show the vanilla, custard and coconut aromas of American oak. The spiciness found on the finish tends to be sweet – like cinnamon or nutmeg. With a little more weight these are versatile whiskies that can be enjoyed at any time.

Rich and Round

There are fruits here as well, but this time they are dried: raisin, fig, date, sultana etc, which shows the use of European oak ex-sherry casks. A slightly drier feel may be detected resulting from the tannins in the oak. These are deep whiskies, sometimes sweet, sometimes meaty and best enjoyed after dinner.

Smoky and Peaty

The smoke aromas found in these whiskies comes from the burning of peat when the malt is being fried, giving way to a whole range of different aromas from soot to lapsang tea, tar, kippers, smoky bacon, burning heather and woodsmoke. Often oily in texture, all peaty whiskies are a great wake-up as aperitifs and can even be enjoyed mixed with soda. Older, richer examples are for later in the evening.

Part: The Art of Blending Whisky

The idea that history is written by the victors doesn’t hold much water with Scotch whisky. As far as an English-speaking audience is concerned, whisky’s history has been that of how single malts were temporarily unspurred by blends, and how the natural order of things has been restored. However, 90% of the Scotch sold in the world is blended, and its sales continue to grow. Blends remain the victor.

That is, however, the wrong way to look at things – blends and malts co-exist happily; they need each other, and they occupy different places in the world of whisky. It cannot be said that one is better than the other – they are different. Malts are about the intensity of character and single malt bottlings are about maximising singularity. Blends, however, are about creating a totality.

In principle, the creation of a blend is a simple one: grain and malt whiskies are added together to give an acceptable, final, flavour. This can easily be done as a one off, and perhaps the result is satisfying, however producing millions of bottles every year – and keeping the blend the same – is challenging. Blenders, therefore, must have an intimate knowledge of their palette of flavours. They must know not just what whisky A tastes like, but what it tastes when put with whisky B, C and D. They need to build in as many options for themselves as possible in order to retain consistency and always be true to the house style.

Because of the perceived victory of single malts, when faced with a blend drinkers want to know what malts are used, how many are in the blend and how old they are. The simple answer is: the right ones, the right number and at the right maturity. Blends are based around flavour and consistency, and how one might get there is not important. The malts are chosen because of the way they interact with other whiskies – some are used for their top notes, others for grip, some for smoothness, others for richness; some for smoke. Some might be in relaxed casks to enhance vibrancy while others might be over wooded to provide grip. Their number is the right one to achieve that flavour profile, which is different to how old they may be.

Whereas age is a statement of time, maturity is concerned with how wood, spirit and air have interacted. Different levels of maturity equal different flavours. Blending is not a numbers game; it is a flavour game and, by having a range of distillery characters, woods and aspects of maturity, complexity is achieved.

Johnnie Walker’s master blender, Jim Beveridge, has always emphasised the transformative power of grain, the manner in which it not only adds its own flavour, but helps tease out new flavours from the different malts in the mix.

Grain is not a filler or a diluting element; it contributes texture and gives a greater unity and coherence to the blend. When you taste a blend, it is the grain that is providing the soft, tongue-clinging element that seems to pull the flavours along; it adds flavour and mouthfeel. Grains are a way to allow the hidden complexities within the malt – and by extension, the blend – to be revealed.

The key isn’t just throwing different flavours and textures together but having an understanding of how these apparently contrasting elements work in harmony with each other, and then how they can be made to suit a serve or an occasion. A blender is not just thinking what goes into a blend but how that blend will be consumed. By and large, blends are not made to be drunk on their own – the majority are created to work at their best when drunk long or mixed in cocktails.

Ready to try a Whisky Cruise?

We offer whisky cruises aboard hotel barges Scottish Highlander and Spirit of Scotland along the Caledonian Canal and Loch Ness, with a special itinerary that allows whisky lovers to visit a number of long-established distilleries to find out more about how Scotland’s favourite export is produced, as well, of course, the opportunity to taste it! Whisky cruises can be taken at any time by a group chartering the barge.

For more information on our itineraries and the rest of our collection of luxury hotel barge cruises, why not order a free copy of our brochure today or speak to a member of our team directly using our handy Contact Form.

English

English

Spanish

Spanish French

French German

German Norwegian

Norwegian Portuguese

Portuguese Swedish

Swedish Italian

Italian Russian

Russian Simplified Chinese

Simplified Chinese Japanese

Japanese