Our experts delve into the history of barges and how it has become one of today’s popular pastimes…

An Insider's Guide to the History of Barges

A History of Barges

The intricacies of barge design has evolved over the centuries, and these unique vessels have been repeatedly refined in order to best accommodate their intended cargo and navigate their working environment with ease. Here’s our guide to the history of barges…

Did you know, one of the earliest known barges was Egyptian, dating from 2500 BC? Officially acknowledged as the Khufu Ship, it was a solar vessel intended for use in the afterlife by King Khufu, the 2nd Pharaoh of the 4th Dynasty, to allow him to travel through the Heavens with the Sun God Ra.

The Romans used barges across their empire, canalising certain sections of rivers to make them more navigable. For example, the Canal de la Robine, which flows through the town of Narbonne in southern France, was built in the bed of the canalised portion of the River Aude. Barges were used to transport goods such as wine and olive oil from around Narbonne as well as amphorae (a jar or jug with two handles and a narrow neck) from the town of Salleles d’Aude to the coast where they were loaded onto galleons and shipped to every corner of the Roman Empire.

Where does the word "barge" come from?

The word “barge” was first attested from 1300 and derived from the Latin “barga”. The word could refer to any small boat, whether it be used for pleasure or for commerce. Later, from the same root, the word “barque” was derived meaning “three-masted sailing ship” and the term “barge” became more associated with the flat-bottomed cargo vessels which we know today.

Telling them Apart

Superficially, many barges look similar. In England, broad beam barges are generally referred to as Humber barges or Thames barges, while all Dutch barges are referred to as just that — Dutch barges. Modern cargo barges, which are mostly Dutch in origin, come in a variety of styles. Some, such as the Luxe Motor and Tjalk Klippers are readily identified by the sweeping line of the hull, whereas the Belgian Péniche and Spitz have a relatively flat deck.

Tjalks, whose name derives from old Dutch meaning “Sailing Vessel”, have been around since the late 17th century. With a shape not dissimilar to a clog, they have seen widespread use as both cargo and passenger carrying vessels since their inception on the waterways of the Netherlands. Originally made from wood, iron Tjalks first saw production by the mid-19th century. By the beginning of the 20th century, the use of steel became more common, resulting in greater strength but with the potential for corrosion.

All modern barges have one thing in common – they were designed to navigate in shallow waters. Some barges were built to carry freight through shallow inland or coastal waterways; some were built for fishing in shallow waters. These barges can go anywhere where there is at least 3ft of water and the fixed bridges are more than 10 or 11 feet above water level.

Barging Throughout Europe

Barges, both on canals and rivers, have played a major role in France’s economy for centuries. By the 19th century the canal network of Europe had links to the English Channel, Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, however a lack of standard dimensions made long-distance journeys difficult.

This changed in 1879 when the Minister of Public Works, Charles de Freycinet, chose to standardise the canal network by ordering an increase in the length of lock chambers, to 39m with a width of 5.2m (approximately 128ft x 17ft). A minimum depth of the basin was also required to be 2.2m (7ft 3in), allowing barges between 300 – 350 tonnes to pass. Likewise, new bridges and other structures built across the waterways had to meet the new standards of measurement. As a result of this standardisation, barges could travel long-distances with their cargo, essentially from the north of Holland and Germany to the south of France.

If one draws a line on the map of Europe starting in St. Petersburg, Russia, and ending in Lyon, France, you could cruise through almost all the inland waterways on the continent to the northwest of this line with the same sized vessel.

The Evolution of Classic Barges

Until the end of the 19th century most barges were either sail powered or towed along canals by the only other form of traction possible at that time, i.e. horse- or manpower. With the introduction of the steam engine in the 19th Century, however, steam tugs appeared, initially towing barges in the estuaries of Belgium and the Netherlands. Seagoing barges which covered longer distances such as the Klippers and Tjalks that were delivering goods to England and Brittany remained under sail until the 20th Century. With the high cost of steam-power, most canal barges still relied on wind, horses and manpower as the most common forms of propulsion until the First World War.

With the improvement of the internal combustion engine after the First World War, many barges were fitted with an auxiliary engine. Modified barges would, at first, retain their sailing rig, but most eventually reduced this to a mast and boom used only to help with loading and unloading of cargo.

The coming of the diesel engine gave barges greater independence from tugs and horsepower. At first engines were not very powerful, and motor ships had to have pointed bows to allow a better cut through the water. This gave birth to the Luxe Motor, whose hull shape characteristics were the same as the tugs, with a sharp bow and a rounded stern.

The accommodation behind the wheelhouse (including a kitchen and a toilet) were thought very luxurious for the time, especially considering that most houses did not have running water or indoor toilets, lending to the name “Luxe”. Barges built from 1920 onwards were usually constructed of steel rather than wood or iron and had an engine from the outset.

The Spitz was originally towed by man/woman, horses, or later by a small steamer, which then towed several barges at a time. After the Second World War a lot of vessels of the Belgian Spitz design received an engine (for many, it was a decommissioned tank engine) and had to be modified at the stern to allow for better steering. Built to the Freycinet standard dimensions, which had been dictated by Napoleon, it was well suited for the canals in the south of the Netherlands, France and Belgium.

Modern Engineering

During the 1920s there was a boom in Luxe Motor construction. The hulls were built of steel in the shape of the previous wooden barges, protected from possible sharp blows when entering locks by rubbing plates and a strong bow. Most were built between 18 and 30 metres (60 – 100 ft) long, however some were lengthened in the 1950s to make them more competitive against the falling price of road transportation.

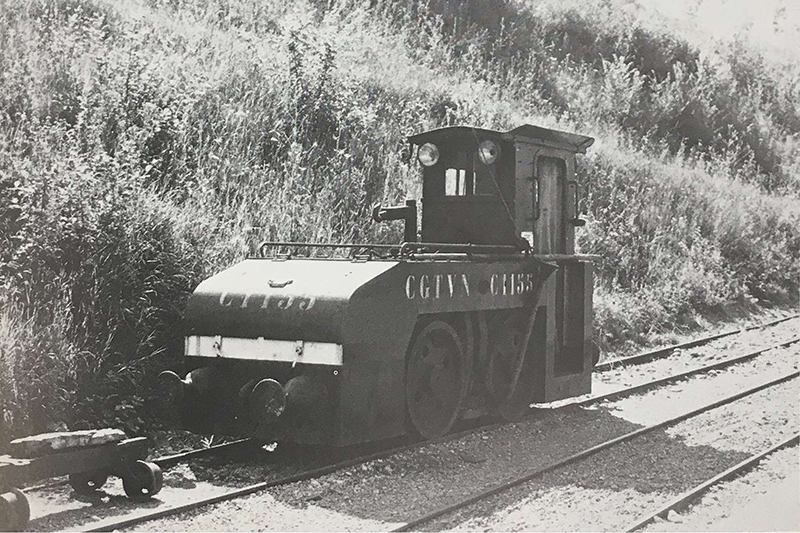

By 1940, a new generation of barges began to appear, equipped with powerful diesel engines. This period represented the zenith of barge building in France, Belgium and the Netherlands. The northern canals in France were also modernized with electric or diesel tractors that could pull non-motorized barges. In some cases, winches with chains lying on the canal bed helped to pull barges through tunnels which lacked tow-paths.

Through the mid 20th century, competition from road and rail transport increased but Freycinet barges still plied the canals and rivers all over the waterways of Western Europe. On larger rivers, a new generation of vessel called “push-boats” gradually replaced the tugs, pushing numbers of barges rafted together. At the same time, however, on quieter canals such as the Canal du Centre in France, manual and animal traction remained in use.

Waterway Tourism

The real decline of water transport in France began in the 1970s, with road and rail taking over and government money being cut back for the canals leading to lack of maintenance and, in some cases, collapse of banks, locks and tunnels. The Freycinet barges were scrapped by the hundreds but fortunately, before things got too bad on some waterways, this period saw the advent of tourism and the birth of self-drive boating holidays and hotel barging.

Waterway tourism has continued to increase, and nowadays a large number of self drive cabin cruisers and our collection of luxury hotel-barges cruise through the most beautiful parts of the canal networks of Europe. Of the many types of Dutch barges built at the turn of the century, the majority are still around. The Luxemotor and the Tjalk are the most sought after and the most expensive because they were built to a high standard and with attractive lines. Many have now also become private floating homes.

Did you know, our L’Art de Vivre hotel barge celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2017? Read more about our own little slice of barging history here.

English

English

Spanish

Spanish French

French German

German Norwegian

Norwegian Portuguese

Portuguese Swedish

Swedish Italian

Italian Russian

Russian Simplified Chinese

Simplified Chinese Japanese

Japanese